Cognitive Neuroscience of Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia is a serious mental illness characterized by a range of symptoms that affect a person's ability to think, feel, and behave clearly. The symptoms of schizophrenia can be grouped into three categories: positive symptoms, negative symptoms, and cognitive symptoms. Positive symptoms include hallucinations, delusions, and disordered thinking. Hallucinations are sensory experiences that are not based in reality, such as hearing voices or seeing things that are not there. Delusions are false beliefs that are firmly held despite evidence to the contrary, such as believing that one is being persecuted or that one has special powers. Disordered thinking can manifest as incoherent speech or disorganized behavior. Negative symptoms refer to a reduction or absence of normal functioning, such as reduced emotional expression, lack of motivation, and social withdrawal. Cognitive symptoms can include problems with attention, memory, and decision-making. The exact causes of schizophrenia are not fully understood, but a combination of genetic, environmental, and brain chemistry factors are thought to play a role.

Cognitive Neuroscience of Schizophrenia

Cognitive function is a critical determinant of quality of life in schizophrenia, and the severity of cognitive symptoms are highly predictive of the prognosis and functional outcomes of schizophrenia. Therefore, understanding the nature and source of cognitive deficits may help identify the most effective treatment approaches. With advances in cognitive neuroscience in the past four decades, there has been a significant increase in research on cognition and the brain dysfunctions in schizophrenia. Cognitive neuroscience is an interdisciplinary field of study that seeks to understand the neural basis of cognitive processes such as perception, attention, memory, language, decision-making, and emotion. Research has shown that deficits in working memory, executive control, episodic memory, motor functions, and sensory perception are consistently found in schizophrenia. Cognitive neuroscience studies of schizophrenia using various psychophysiological and functional neuroimaging methods have extended our understanding of the brain substrates of the cognitive deficits. Largely, there are two main hypotheses/approaches have studied cognitive deficits in schizophrenia regarding 1) top-down cognitive deficits associated with the prefrontal cortical dysfunctions and 2) bottom-up cognitive deficits associated with sensory cortical dysfunctions. Also, the brain network dysfunctions in micro, meso, and macro-level brain circuits have been consistently reported in people with schizophrenia.

Context-Processing & Working Memory Deficits in Schizophrenia

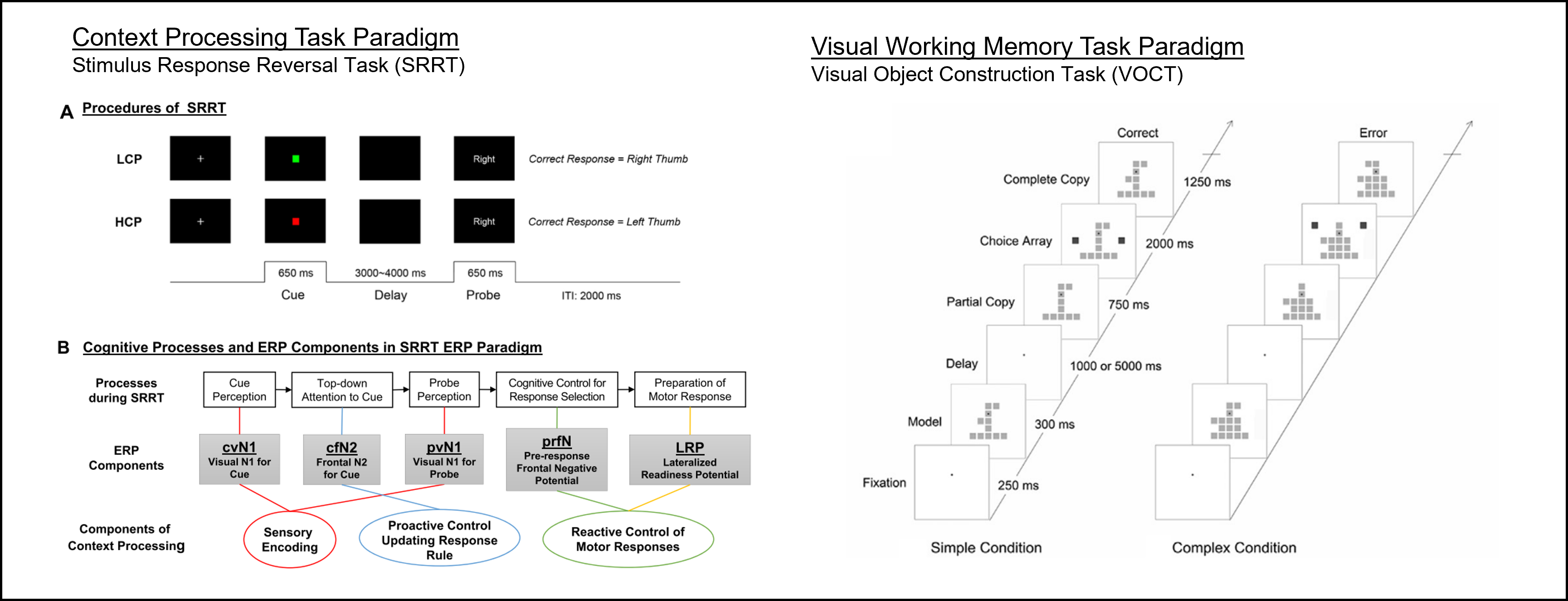

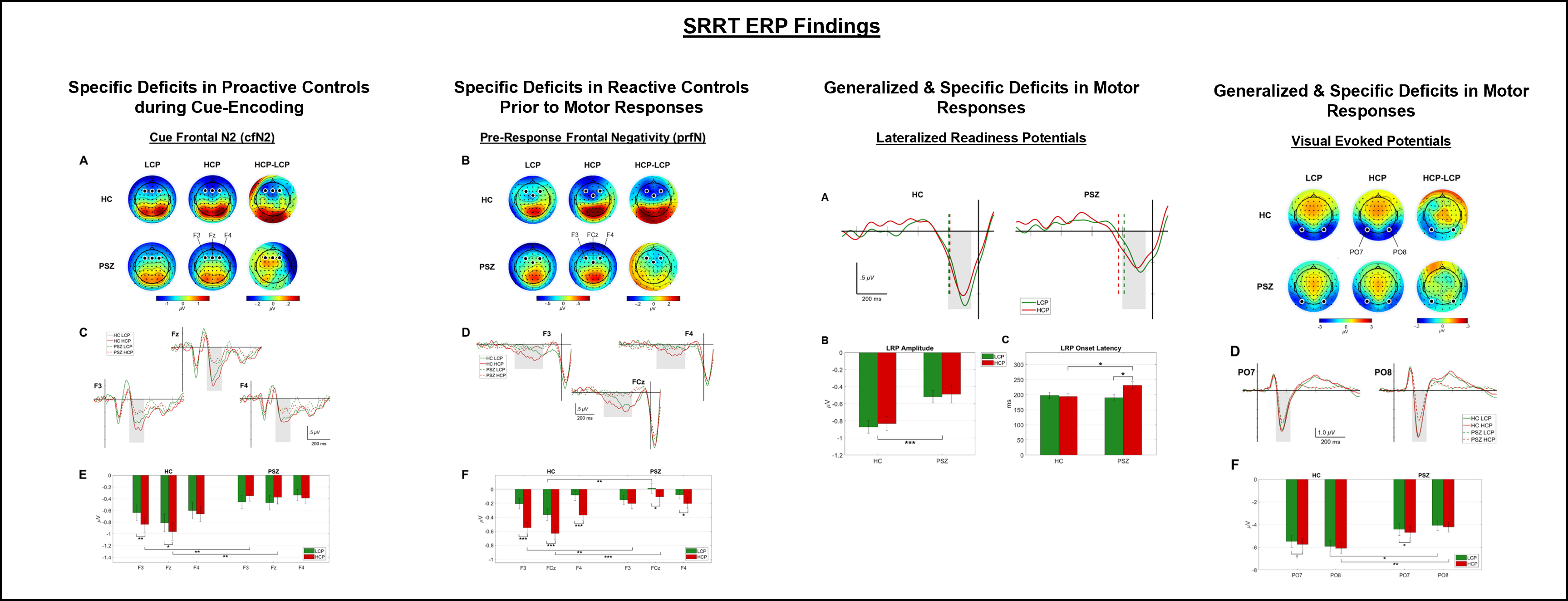

A deficit in context processing and the associated prefrontal network dysfunction has been identified as central to schizophrenia. Context processing involves the control of behaviors according to goals or other stored abstract representations that reflect contextual information (e.g., rules) and is considered an executive function related to goal representation. According to the Dual Modes of Cognitive Control (Braver, 2012), there are two modes of cognitive controls, including Proactive & Reactive controls. The former includes early selection of goal-relevant information to update contextual rule & active maintenance of the rule, while the latter involves detection & resolution of behavioral conflicts at the time a response is required. Therefore, working memory deficits also contribute to context processing, especially proactive controls.

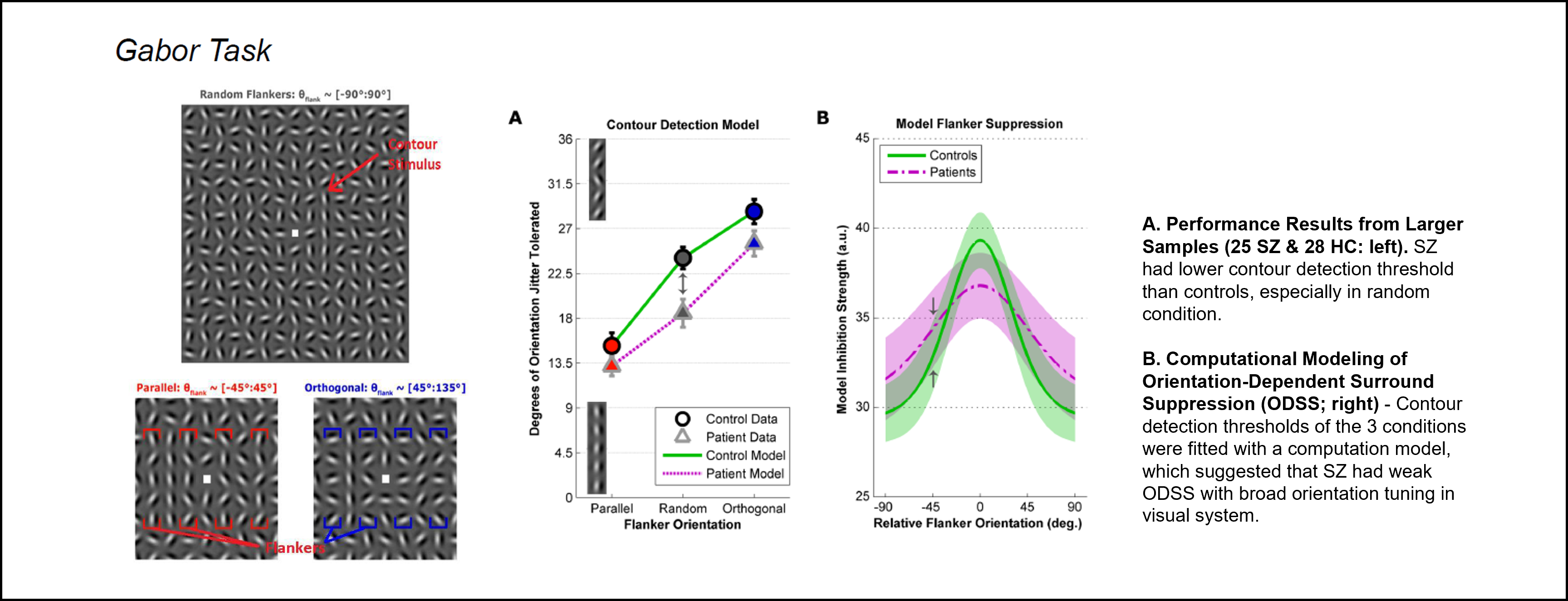

Visual Perception Deficits in Schizophrenia

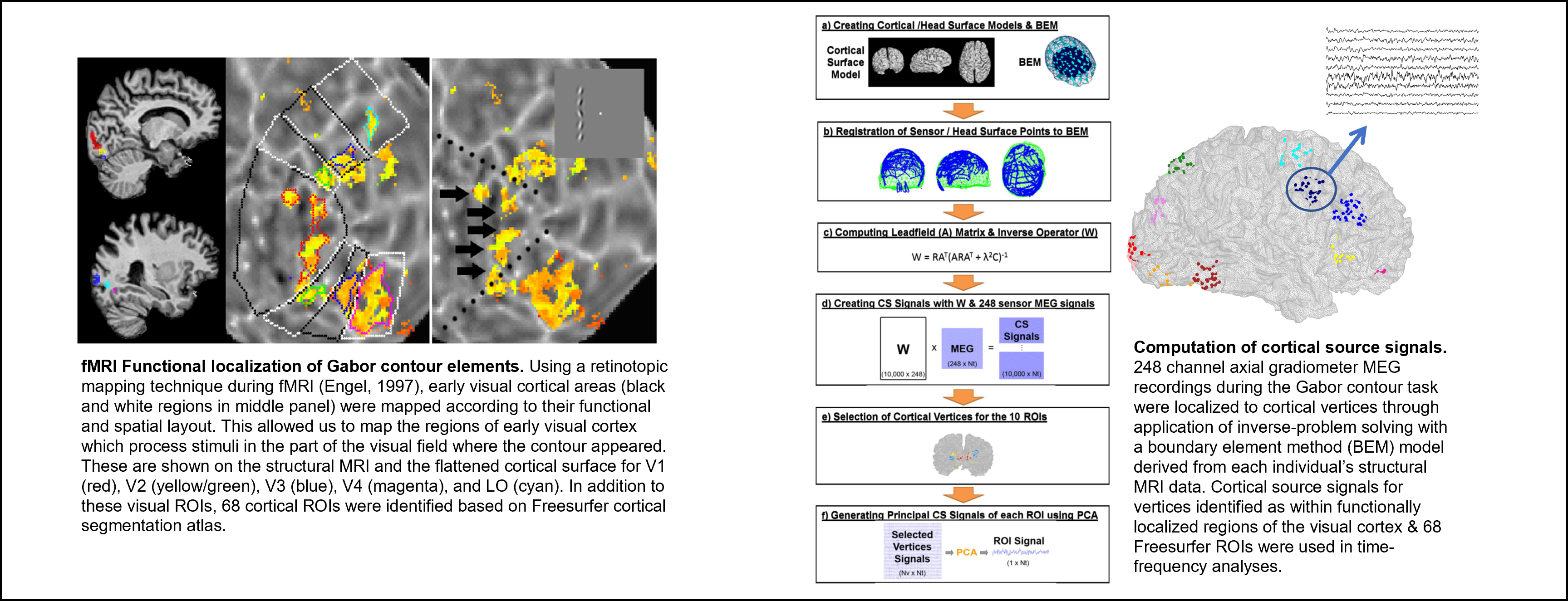

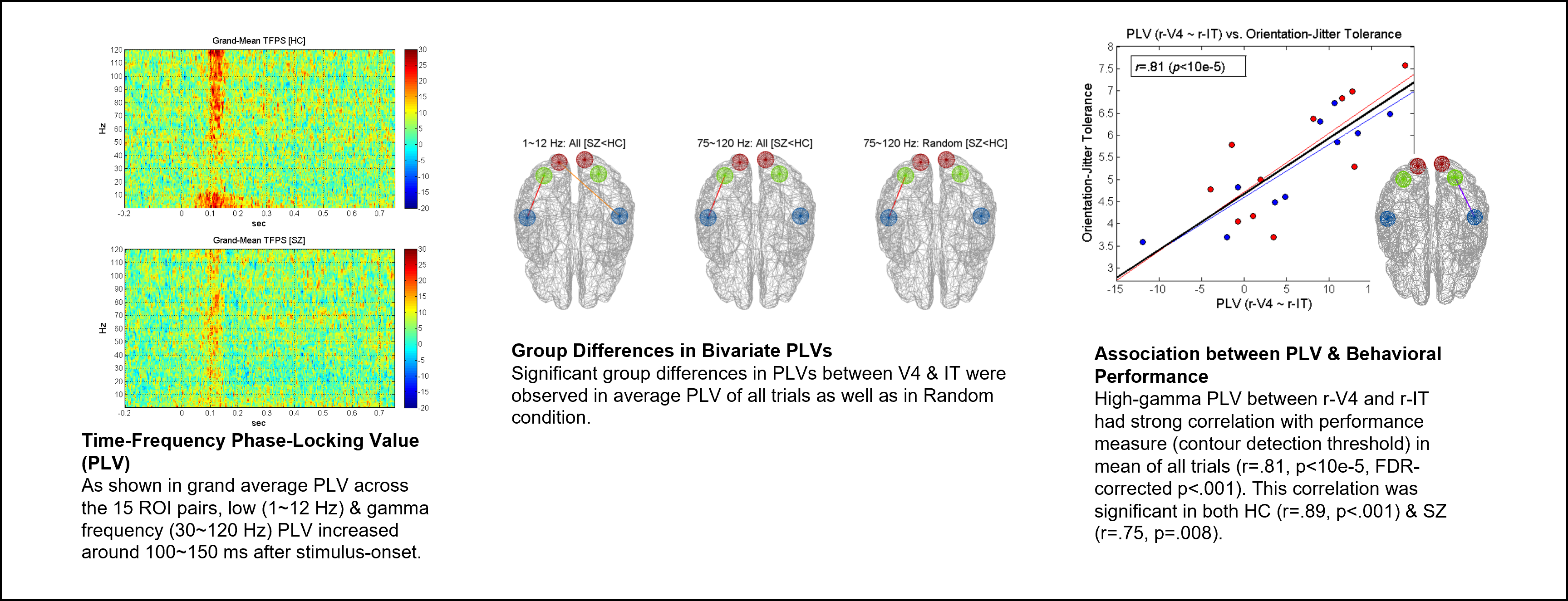

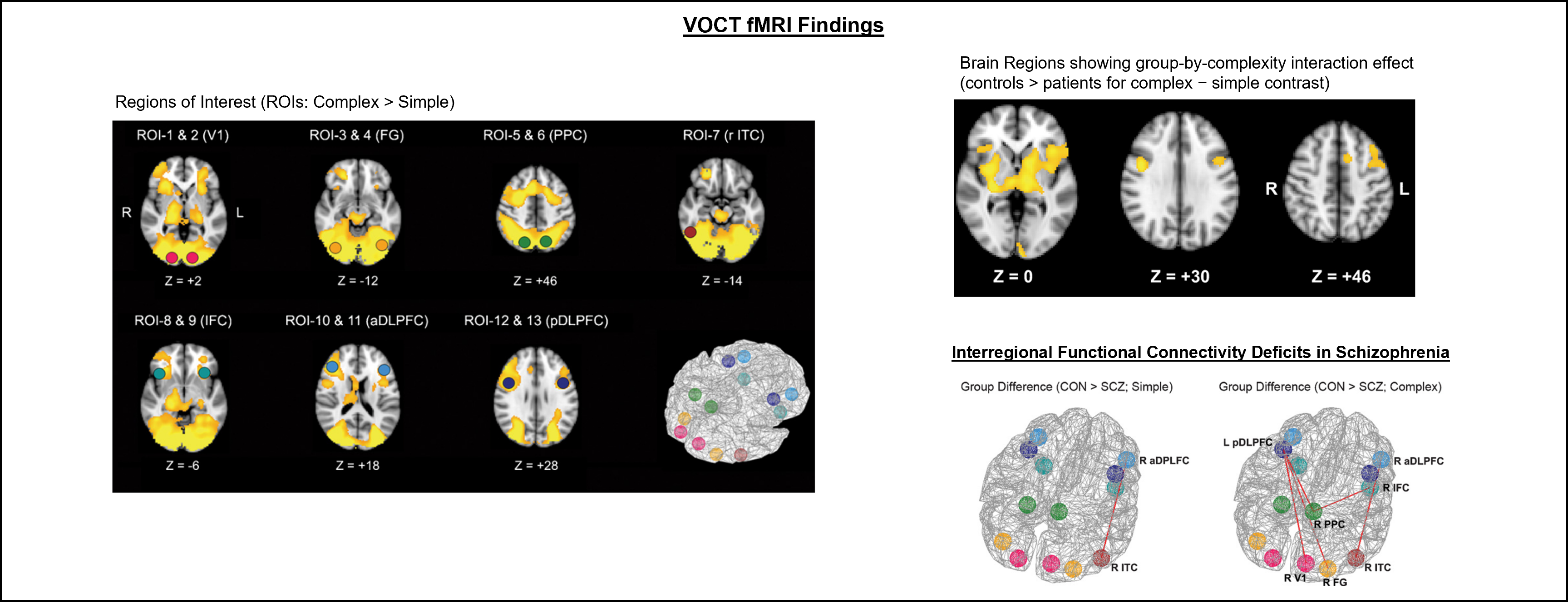

People with schizophrenia (SZ) have been known to have visual perception abnormality (Butler et al., 2008). In particular, SZ have difficulty detecting contours within a display of visual stimuli (e.g., dots). Contour detection deficits have been associated with disorganization symptoms as well as reduced activations in visual cortical regions V2 and V4 (Silverstein, et.al., 2009). The deficit may reflect characteristic neuropathology central to schizophrenia. Visual context created by the orientation of nearby stimuli (i.e., flankers) affects the likelihood a contour will be perceived. Contextual modulation by flankers appears dependent on inhibitory functions of the visual cortex. Recently we found that SZ had deficits in contour detection, which was modulated by contextual flankers (Schallmo et al., 2013). Using a visual contour detection task, fMRI scans, and MEG recordings, we found that people with schizophrenia had the local and interregional neural synchrony during visual contour detection, which explained their task performance deficits.